When I lived in Madrid, visitors would often return to my flat in a state of art exhaustion having ‘done’ the Prado or Reina Sofia museums. Trips to both are entirely understandable since they boast superb collections, but for my money neither could really compare to the much smaller, much more personal (and happily much nearer to my flat) Sorolla Museum.

Joaquín Sorolla – the 19th century Spanish painter dubbed the ‘Master of Light’ by Claude Monet – loved working in the open air, especially capturing the sun-drenched beaches of Valencia. Yet ironically, he also had a marvellous studio at his home in Madrid just around the corner from me. With its high ceilings, fabulous four-poster day bed, and beautiful garden just outside its windows, it makes for a very evocative visit. And one which doesn’t wallop you with museum fatigue.

To be honest, while I do like the expansiveness and the almost limitless options of a major art gallery or museum, I usually find their smaller counterparts more rewarding since they give me a historic sniff of the artist at work.

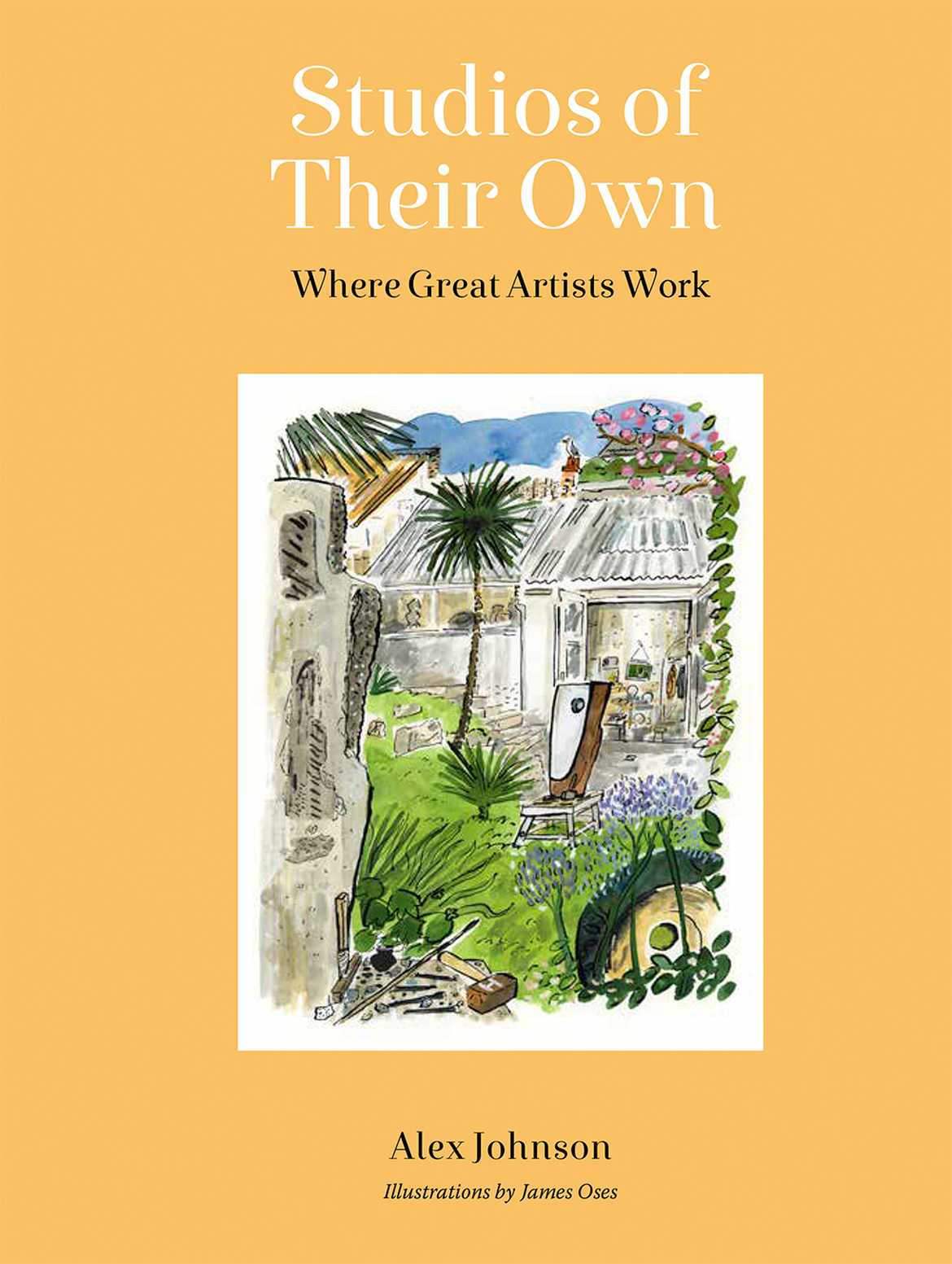

A historic sniff and a polite poke around the creative nerve centres of painters, sculptors, photographers, installations artists (and a quilter) is what I hope my latest book Studios of Their Own provides for readers. Beautifully illustrated with original watercolours by artist James Oses, together we look at the places around the world where masterpieces have been created.

“Writers stamp themselves upon their possessions more indelibly than other people,” wrote novelist Virginia Woolf in her 1911 book Great Men’s Houses, “making the table, the chair, the curtain, the carpet into their own image.” I think the same is true of artists, that the ritual of going to a special place to work – what Woolf famously called “a room of one’s own” - is a key part of who they are. And this is true for more than world famous ones. During lockdown many of us discovered that what we really needed was a separate space in which to express ourselves.

As the visitor figures for the National Trust continue to indicate, there is plenty to be experienced in the room where it happened, the views artists looked out on, the chairs they relaxed in, the unique atmosphere they built up that in its turn helped them create. These places offer us curious travellers more than just a chance to root around the studios of the rich and famous. They provide a biographical behind the scenes insight into what was especially meaningful for them in their most private havens.

The opening up of these properties give us the chances to be a part of these artists’ lives, take a look at the books on Frida Kahlo’s shelves, relax at the familiar amount of clutter on Francis Bacon’s desk (well, hopefully not too familiar). If it’s intriguing to take a close look at a friend’s kitchen, how much more so is standing in the dining room where René Magritte’s imagination took flight. These objects and spaces were eyewitnesses to remarkable creativity, as good as any biography for getting close to their minds. There’s also the faint hope that perhaps some of the magic will rub off…

The concept of a studio has changed considerably over time, as I hope our book shows. Even the word itself is fairly new in terms of designating the space where artists work, not properly in use until the late 1600s in Italy and in Britain from about 200 years later. Like everything, it has been moulded by the march of technology, not least by the 19th century advances in how paints could be stored in metal tubes enabling artists to get out of the studio and into the great outdoors. Transportation developments allowed Georgia O’Keeffe to use her car as a mobile studio and Claude Monet to drift down the river, painting in a kind of shed-boat.

But what has not really changed is the importance that artists attach to their workspace. According to the writer and photographer Maxime de Camp, Eugène Delacroix, featured in Studios of Their Own, “loved only his studio and it was there he preferred to live.” “Of my sister at work, we saw very little,” wrote John Greenaway about his artist and illustrator sister Kate. “She very wisely made it a fixed rule that, during working hours, no one should come into the studio save on matters of urgency.”

Indeed, the studio has also been a crucially important place for female artists who have historically been barred from centuries of a male-run art world and its academies. Having just such a “room of one’s own” afforded them a valuable space in which to prove their expertise.

Studios are often transient spaces. Some of the studios in the book are long gone now, demolished, or totally repurposed. It would have been quite something to visit the studio envisaged by Duncan Grant for Vanessa Bell’s home in Gordon Square, London. She wrote to her husband Clive in December 1912 that her lover Grant’s plan was “to turn my studio into a tropical forest with great red figures on the walls - a blue ceiling with birds of paradise floating from it (my idea), and curtains each one different.” Grant also wanted to include a bath in the floor. Charleston, the rural habitat of the Bloomsbury set in Sussex where Bell enjoyed painting, is perhaps a little less exuberant but fortunately very much still with us and one of my favourite revisits.

The good news is though that you can still visit plenty of these workplaces, as the extensive Artist’s Studios Museum Network proves. Painter Walter Sickert said of plans to museums Sir Frederick Leighton’s house, “Do not let us consecrate in perpetuity the hotel, now that the brilliant guest has gone”, but the truth is that artist museums make a huge effort to maintain the atmosphere of a working studio where the artist in question has merely stepped out for a moment, leaving you free to step in.